Journey to Hill 481

2October 1, 2013 by Lydia Syson

Last week’s experience of visiting some of the settings for key events in A World Between Us was extremely powerful. It’s certainly a strange sensation to go to a real place for the first time after having imagined it so intensely and for so long. These are all places of real and terrible tragedies, yet hope and idealism are equally significant elements in their histories.

I thought I might feel frustration and regret at an opportunity missed, or chastise myself for what I’d left out or got wrong. Perhaps I’m finally far away enough from the writing process to look back with just a small sigh of que sera sera. Anyway, as it turned out, almost exactly a year since the story of Felix, Nat and George was published, I found myself enjoying a kind of recognition I’d not encountered before, and felt I’d come at last to the Ebro with a richness of knowledge and understanding I could never have brought with me at an earlier stage of researching and writing the book. Of course I thought a lot about my imaginary characters while I was in Spain. But I felt more involved still with the real people who had originally inspired A World Between Us, details of whose stories continue to emerge even after their deaths.

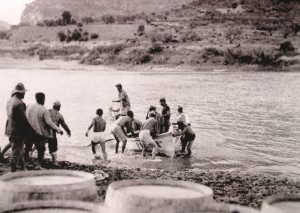

Between the commemorative events at the cave hospital at La Bisbal de Falset and those at Corbera Old Town we went to the wooded banks of the Ebro river, near Ascó, a stone’s throw from the  spot where Nat crossed in darkness before the well-planned and much-anticipated attack on Nationalist territory in July 1938.

spot where Nat crossed in darkness before the well-planned and much-anticipated attack on Nationalist territory in July 1938.

‘Even after night has fallen, heat rises from the dry earth with a force you can wade through. The river is cooler, almost cold. Nat feels its darkness swirl and eddy against his fingertips as he grips the side of the small boat, so low in the water that it sets his nerves jangling. He’s never learned to swim. The Ebro is deep and broad, and its currents are strong.’

A World Between Us, p. 225

On a sunny late summer day, under blue skies unthreatened by aviones, the speed and width of the river still looked daunting. I stood on a pontoon alongside people whose own parents had been rowed into enemy territory that stifling night, and wondered. Many of the Brigaders who took part in this offensive had been forced into the Ebro’s fast-flowing waters just a few months earlier, during the chaos and terror of the Retreats. John Longstaff had been the very last across the bridge at Mora de Ebro before it was blown up by British engineer Percy Ludwick and his team, and never forgot the urgent cries of ‘Venga! Venga!’ as he sprinted to safety. Former Olympic rower Lewis Clive, who was later killed outright on Hill 481, had swum across with one non-swimmer, and returned to rescue military equipment. Others were swept away by the current.

Duncan Longstaff, the main organiser of this IBMT tour of the Ebro, was one of many who told me last week of the frustration of how little his father had spoken about the Spanish Civil War when he was growing up. A common lament – which I share in relation to my own grandparents and their anti-fascist activities in London – was not knowing the right questions to ask at the right time. I’d first encountered John Longstaff in the sound archive of the Imperial War Museum. He was a former Stockton hunger-marcher who became a runner for the British Battalion and, if I remember rightly, like Nat, he first saw action at Jarama in February 1937. He recalled the drama of the wordless Ebro crossing in a written memoir:

We got into rowing boats; everyone was silent and thinking about the fighting to come. The Spanish and International Brigaders had muffled even the oars. I had a lot of equipment, a rifle, about 100 rounds of ammunition and my blanket tied round my body. Inside the blanket I carried my few odd personal items, including an empty mess tin and a filled water bottle.

(quoted in Richard Baxell’s Unlikely Warriors: the British in the Spanish Civil War and the Fight Against Fascism)

The muddle of anticipation, longing, disconnection and sheer fear of this moment was brilliantly captured by James Jump in a poem which his son Jim kindly allowed us to use in the AWBU iBook:

‘Ebro Crossing’ by James Jump is one of a number of poems included in the multitouch iBook edition of ‘A World Between Us’ from the magnificent collection ‘Poems from Spain: International Brigaders on the Spanish Civil War’ by kind permission of the editor, Jim Jump.

‘Night. They wait for news and hope for back-up. Men come, scrambling through the darkness. One has a vast reel of wire on his back, unspooling as he clambers up. With telephone contact, news filters through. Don’t move. We’ve got Gandesa almost surrounded. They’re waiting for us. Depending on us. Fresh ammunition? Food? Not much. The Fascists have opened the flood gates, you see. The Ebro is rising. Pontoons swept away, boats unmoored. Some mules on their way. A little water. Not enough. Cigarettes.

‘Night. They wait for news and hope for back-up. Men come, scrambling through the darkness. One has a vast reel of wire on his back, unspooling as he clambers up. With telephone contact, news filters through. Don’t move. We’ve got Gandesa almost surrounded. They’re waiting for us. Depending on us. Fresh ammunition? Food? Not much. The Fascists have opened the flood gates, you see. The Ebro is rising. Pontoons swept away, boats unmoored. Some mules on their way. A little water. Not enough. Cigarettes.

The wounded are dragged away.’

A World Between Us, p. 236.

On Hill 481, where the pines are now thicker and the cover less sparse than it was in 1938, it is easy to see how horribly exposed the men were, as they repeatedly tried and failed to take this position from the Nationalists. It’s much further from the river than I realised, and the church tower at Gandesa from which the enemy also fired seems implausibly distant too. Rosemary still grows on the hillside. We have a moment of silence and reflection at the top, and then sing. Si me quires escribir…

In the new town of Corbera d’Ebre there is an impressive museum, one of a number of historical ‘spaces’ in the area known as the ‘Espais de la Batalla de l’Ebre’. It’s called 115 days. You get a real sense of what it was like to live through these days, from both a military and domestic point of view. Empty plates wait forever for food on the table of a kitchen that’s been abandoned in haste. A soldier writes a letter in a trench. Newspapers announce the Munich agreement. Suitcases are packed for flight. There is even a wooden crate which once held the ubiquitous condensed milk tins to which almost every nurse refers…the tins which became coffee cups, oil lamps, anything anyone could think of or need.

forever for food on the table of a kitchen that’s been abandoned in haste. A soldier writes a letter in a trench. Newspapers announce the Munich agreement. Suitcases are packed for flight. There is even a wooden crate which once held the ubiquitous condensed milk tins to which almost every nurse refers…the tins which became coffee cups, oil lamps, anything anyone could think of or need.

We were staying in Cambrils, at first sight an unexceptional seaside town on the Costa Dorada. But then I realised…all those stories told by volunteers of the slow train down the coast from Barcelona to the IB HQ at Albacete, a train so slow you could get out and pick oranges and hop back in, a train greeted by flowers and food and warm welcomes throughout its journey? It passed through here.

After the retreats the International  Brigade was headquartered at the castle here (now a restaurant) and during the battle of the Ebro, the wounded (John Longstaff included) were treated at the hospital which had once been a seminary. Thanks to Cambrils Museum historian Gerard Martí and archivist Montserrat Flores, who have spent years gathering material about the impact of the war in this area, we heard how local people now in their 80s and 90s still remember the arrival of the Brigaders in their village in their childhood – fresh vegetables and eggs were exchanged for precious tinned meat, a Christmas party was held, with a Brigadista assigned to each child and presents for all, and before battle, a mass was even celebrated in the chapel, attended by villagers and some of the Catholic Polish volunteers.

Brigade was headquartered at the castle here (now a restaurant) and during the battle of the Ebro, the wounded (John Longstaff included) were treated at the hospital which had once been a seminary. Thanks to Cambrils Museum historian Gerard Martí and archivist Montserrat Flores, who have spent years gathering material about the impact of the war in this area, we heard how local people now in their 80s and 90s still remember the arrival of the Brigaders in their village in their childhood – fresh vegetables and eggs were exchanged for precious tinned meat, a Christmas party was held, with a Brigadista assigned to each child and presents for all, and before battle, a mass was even celebrated in the chapel, attended by villagers and some of the Catholic Polish volunteers.

There were other surprises. At a time  when the worst excesses of anti-clericalism were being unleashed in Catalonia and Aragon in particular, the President of the Anti-Fascist Committee barred the door of the huge modern seminary where he’d been educated himself and insisted it should be saved from burning. (The brothers who taught there had already been safely hidden.) Of course the building made a perfect hospital, and to this day, little has been touched. As we stood in a glassed corridor, it was all too easy to imagine the amputated limbs raining down from the operating theatres above, witnessed in horror and never forgotten by a fourteen-year-old cook working in the kitchens below.

when the worst excesses of anti-clericalism were being unleashed in Catalonia and Aragon in particular, the President of the Anti-Fascist Committee barred the door of the huge modern seminary where he’d been educated himself and insisted it should be saved from burning. (The brothers who taught there had already been safely hidden.) Of course the building made a perfect hospital, and to this day, little has been touched. As we stood in a glassed corridor, it was all too easy to imagine the amputated limbs raining down from the operating theatres above, witnessed in horror and never forgotten by a fourteen-year-old cook working in the kitchens below.

(I wish I had time to include all the other stories from the Ebro I heard during this visit, such as those of the Yugoslav volunteer Danilo Lekic, Clarence Kailin and his best friend John Cookson. Do follow these links to explore further…these are people well worth finding out about.)

Category News | Tags: 115 days, Battle of the Ebro, British Battalion, Cambrils, Clarence Kailin, Corbera d'Ebre, Danilo Lekic, Gandesa, Gerard Martí, Hill 481, James Jump, John Cookson, John Longstaff, Lewis Clive, Montserrat Flores, sense of place, Spanish Civil War, UKYA, Unlikely Warriors

Very interesting piece.

Thank you for the link to the IWM archive – John Longstaff is from my hometown, so hearing his experiences make it even more relevant on that count. I wasn’t sure to what extent people from the north east made it over with the IB so this adds a new facet to my understanding of local history.

Louise

Thank you very much, Louise. I know the International Brigade Memorial Trust is working towards compiling a digital archive along the lines of that maintained by the Abraham Lincoln Brigade/Battalion Archives and eventually it be easier to discover these local histories. Meanwhile, the ‘Roll of Honour’ (http://www.international-brigades.org.uk/content/roll-honour) lists the men (not the nurses!) who died in or as a result of the war – about a fifth of volunteers – and records indicate only one each man’s last place of residence. Although the vast bulk came from London, Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool, and the mining communities of South Wales, you’ll see the volunteers had an amazing spread of origins, and quite a few came from the north east.