Remembering the Battle of the Ebro, September 1938

4September 26, 2013 by Lydia Syson

‘On the other side of the river, spirits are high. They’ve driven Franco’s forces from the steep hillsides outside Corbera. But everyone knows Fascist reinforcements will soon arrive and it’s no surprise when the crash and boom of bombardments steps up a day later. The men scan the skies, and wonder if the German and Italian planes have got the trick of breeding. Nat sees fear rising in the eyes of lads who have not fought before, and he does his best to steady their nerves.

These rocky slopes give little reassurance.‘

A World Between Us, p. 234.

The old town of Corbera remains a ruin.

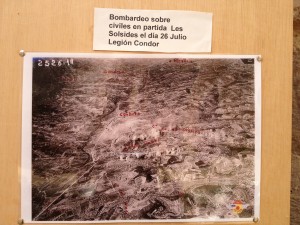

It was bombed  to destruction by the Nationalists seventy-five years ago in the tragic final stages of the Spanish Civil War. Now the Poble Vell stands as a poignant reminder of the cruelty of this conflict, a memorial both to several thousand people who once lived here, and to the tens of thousands who died fighting on the battlefields around. Many of them were boys of just fifteen or sixteen – the so-called Baby Bottle Brigade, La Quinta del Biberón, whose singing as they leave for the front is heard by Felix and Kitty. (AWBU, p229) The silent streets of Corbera Old Town house a series of artworks – an ‘alphabet of freedom’ – while a new exhibition in the roofless church allows visitors to absorb the story of the war from the perspectives of Spaniards and international volunteers alike.

to destruction by the Nationalists seventy-five years ago in the tragic final stages of the Spanish Civil War. Now the Poble Vell stands as a poignant reminder of the cruelty of this conflict, a memorial both to several thousand people who once lived here, and to the tens of thousands who died fighting on the battlefields around. Many of them were boys of just fifteen or sixteen – the so-called Baby Bottle Brigade, La Quinta del Biberón, whose singing as they leave for the front is heard by Felix and Kitty. (AWBU, p229) The silent streets of Corbera Old Town house a series of artworks – an ‘alphabet of freedom’ – while a new exhibition in the roofless church allows visitors to absorb the story of the war from the perspectives of Spaniards and international volunteers alike.

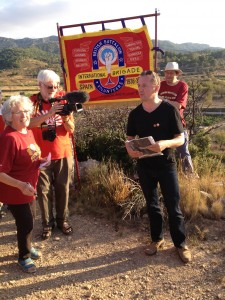

At a moving ceremony I attended here a few days ago, on the anniversary of the last day of fighting for the British Battalion of the 15th Brigade, relatives of Brigadistas and Spanish Republican soldiers testified to their commitment to keeping alive the memories of those dark

At a moving ceremony I attended here a few days ago, on the anniversary of the last day of fighting for the British Battalion of the 15th Brigade, relatives of Brigadistas and Spanish Republican soldiers testified to their commitment to keeping alive the memories of those dark  days. Jordi Palou, director of the organisation Memorial Democràtic, spoke of the increasing need to demonstrate solidarity in the face of the rise of violent Fascist attacks in Europe today. During the five days I’ve just spent in the Ebro region, I’ve been struck by repeated tales of vandalism to so many physical commemorations of the 1930s struggle for democracy: in some places, locals keep the exact location of graves and memorials a closely guarded secret for this very reason. Security has been a concern in the design of the new plaque that was unveiled just outside the church, at a beautiful spot overlooking the valley where some the worst of the fighting took place. Its inscription is in Catalan, English and Spanish. (Under Franco, you could not speak Catalan in public.)

days. Jordi Palou, director of the organisation Memorial Democràtic, spoke of the increasing need to demonstrate solidarity in the face of the rise of violent Fascist attacks in Europe today. During the five days I’ve just spent in the Ebro region, I’ve been struck by repeated tales of vandalism to so many physical commemorations of the 1930s struggle for democracy: in some places, locals keep the exact location of graves and memorials a closely guarded secret for this very reason. Security has been a concern in the design of the new plaque that was unveiled just outside the church, at a beautiful spot overlooking the valley where some the worst of the fighting took place. Its inscription is in Catalan, English and Spanish. (Under Franco, you could not speak Catalan in public.)

Following the announcement by the Spanish Republic on 21 September 1938 that all International Brigade volunteers would be withdrawn from its army, the British Battalion of the XV Brigade fought for the last time next to the road between two and three kilometres east of Corbera d’Ebre before being withdrawn on 24 September. In those final three days of fighting, 23 of the British volunteers were killed along with more than 175 of their Spanish comrades in the battalion.

Then follows the final lines of Cecil Day-Lewis’ poem, ‘The Volunteer‘:

Beyond the wasted olive-groves

The furthest lift of land,

There calls a country that was ours

And here shall be regained.

Volunteers came to Spain in their thousands to fight for equal rights and social justice for all. Vicente Gonzàlez, President of the Asociacion de Amigos de las Brigadas Internacionales, spoke of the spirit of altruism that brought them here, in ‘the biggest act of international solidarity in human history’. Yet even while the International Brigaders were dying alongside the men, women, and children of Spain, the ‘democratic’ governments of Britain and France were doing deals with Hitler and Mussolini in Munich, as Jim Jump of the IBMT reminded us.

Jim stressed the importance of preserving the principles for which the International Brigades were prepared to give so much. ‘We still carry these values in our hearts’, he said. This memorial and others will contribute to transmitting the Brigaders’ ideals to future generations.

Mary Greening, IBMT secretary, was one of two children of British Brigaders who unveiled the plaque. She had already read from the memoirs of her father Edwin Greening, which capture vividly the utter and unremitting horror of the fighting. Jo Yurek, the daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brigadista Steve Nelson, made the point that everyone should have the right to know their personal history. This is a human right, she said, which has been denied to too many.

Mary Greening, IBMT secretary, was one of two children of British Brigaders who unveiled the plaque. She had already read from the memoirs of her father Edwin Greening, which capture vividly the utter and unremitting horror of the fighting. Jo Yurek, the daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brigadista Steve Nelson, made the point that everyone should have the right to know their personal history. This is a human right, she said, which has been denied to too many.

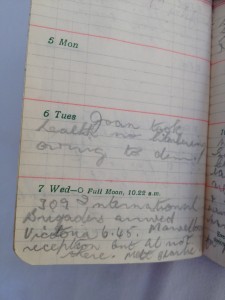

For some, it’s a journey that has just begun. Geraldine Puxty found her mother’s 1938 diary by chance earlier this year. Although she was aware that her formidable aunt Kath (Hobbs) had nursed in Spain, she knew little about her uncle Al, and was intrigued by a diary entry made on December 7th:

‘International Brigaders arrived

‘International Brigaders arrived  Victoria [Station] 6.45. Marvellous reception but Al not there.’

Victoria [Station] 6.45. Marvellous reception but Al not there.’

He never did come back. Uncle Al, as Geraldine knows him, never knew his niece: he died of wounds sustained here on the very last day of the fighting, and lies, like so many other victims of this war, somewhere in Spanish soil in an unmarked grave. Aged 19, Albert Hobbs, a comfortably-off mechanic from Maldon, arrived just in time to fight the bloodiest battle of the Civil War, 115 days of hellish attrition. He’d tried and failed to persuade Geraldine’s father to volunteer with him. She has spent the past week piecing together the fragments of his story, looking for his name on lists.

Later that afternoon, Geraldine collected some earth to take back to  the family grave in Essex, at the British Brigaders last battle position, where a wreath and flowers in the Republican colours were ceremonially laid. Gideon Long, grandson of Sam Wild, the British Battalion’s final commander, spoke of his own journey of discovery and its significance to him, and finished with the words of journalist Martha Gellhorn (The Face of War, 1959), written after twenty years of defending the ‘Causa’:

the family grave in Essex, at the British Brigaders last battle position, where a wreath and flowers in the Republican colours were ceremonially laid. Gideon Long, grandson of Sam Wild, the British Battalion’s final commander, spoke of his own journey of discovery and its significance to him, and finished with the words of journalist Martha Gellhorn (The Face of War, 1959), written after twenty years of defending the ‘Causa’:

I am tired of explaining that the Spanish Republic was neither a collection of blood-slathering Reds nor a cat’s-paw of Russia. Long ago I also gave up repeating that the men who fought and those who died for the Republic, whatever their nationality and whether they were Communists, anarchists, Socialists, poets, plumbers, middle-class professional men, or the one Abyssinian prince, were brave and disinterested, as there were no rewards in Spain. They were fighting for us all, against the combined force of European fascism. They deserved our thanks and our respect and got neither.

Finally, of course, there was singing: ‘The Internationale’ and ‘There’s a Valley in Spain called Jarama’. Brenda O’Riordán, daughter of Irish volunteer Michael O’Riordán of the Connolly Column, also sang ‘The Minstrel Boy’. You’ll find the words here, but do also listen to her recording of that song and you will understand why tears were so close to the surface as the shadows lengthened.

I’m extremely grateful to all the individuals and organisations which worked together to make this and related events in the region this past week possible: the International Brigade Memorial Trust, the Asociación de Amigos de las Brigadas Internacionales, No Jubilem La Memória, the Friends of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade & ALBA, Memorial Democràtic, the Municipal Archive and the History Museum of Cambrils. The energy, commitment and passion of Duncan Longstaff and Almudena Cros in marshalling the troops and getting us all from place to place with grace and humour were quite astonishing. More stories and images to follow over the next few days, and further information about Tuesday’s commemoration here. If you’d like to support the work of the IBMT, why not become a member?

Category News | Tags: 15th International Brigade, AABI, Albert Hobbs, Battle of the Ebro, British Battalion, C Day Lewis, Corbera, Edwin Greening, IBMT, Martha Gellhorn, Michael O'Riordan, Poble Vell, Sam Wild, Steve Nelson, The Volunteer

All this is very moving and wish my ma could have read this! My uncle walked half-starved from the Ebro to his family Barcelona – he was barely 17 and had been a promising scholar before the war. He was so thin when he got home they didn’t recognize him. My Catalan mother born in 1924, who came to England in the 50s and died in Essex in 2008, like Martha Gellhorn got tired of explaining that Franco was originally a rebel who with the help of mercenaries Morroco and later Hitler and Mussolini, had unbelievably managed to overthrow a democratically -elected progressive Republican government. That Spanish Republic had made a brave attempt to modernize Spain, inspired by the French model, and being democratic had the likes of English-style conservative industrialists from Catalonia, liberal-minded professionals in addition to Socialists and the Left supporting it.

A very moving event.

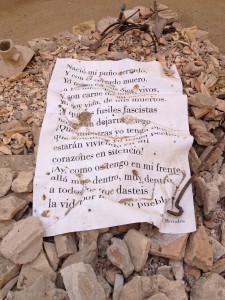

Vientos del pueblo me llevan

Exactly. ‘Vientos del pueblo me llevan’ (‘Winds of the people bear me’, 1937) is a poem by Miguel Hernández, which ends with these words:

Si me muero, que me muera

con la cabeza muy alta.

Muerto y veinte veces muerto,

la boca contra la grama,

tendré apretados los dientes

y decidida la barba.Cantando espero a la muerte,

que hay ruiseñores que cantan

encima de los fusiles

y en medio de las batallas.

If I die, may I die

with my head held high.

Dead and twenty times dead,

my mouth against the wild grass,

I will have my teeth clenched

and my jaw resolute.

Singing I await death,

for there are nightingales that sing

above the guns

and in the midst of battles.

Hernandez died of TB in prison in 1942, three years into a thirty year sentence, during which his poetry was successfully smuggled out of his cell. A cultural officer for the Republican army during the war, he captured the spirit of the ordinary soldier in poems and newspaper articles which were an inspiration for thousands, but he was taken prisoner after Franco’s victory in 1939 while trying to return to his wife and young child. Hernandez is one of the poets represented in the artworks currently on show in the ruined church at Corbera, along with Pablo Neruda, Rafael Alberti, Joan Perucho, Antonio Machado and others. You can read more of his beautiful poetry in Spanish and English and find out more about Herndandez at the website ‘There are Nightingales that Sing’: https://sites.google.com/site/nightingalesthatsing/home