Questioning the Triumph of Abolition

1February 27, 2013 by Lydia Syson

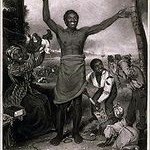

A few years ago I did some research for my children’s South London primary school about a local hero called Dr Lettsom – an eighteenth-century Quaker physician born in the West Indies who freed his slaves as soon as he inherited them in 1767, set up a soup kitchen and a dispensary for London’s poor, and gave away his wealth almost as fast as he made it. A ‘good’ and inspiring story from history. In 2007 the school celebrated the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave  trade by making a ‘Freedom Sculpture’ with the help of a local artist and blacksmith – it’s a beautiful iron butterfly, and every child in year 5 at the time designed and made one of the coils of its wings.

trade by making a ‘Freedom Sculpture’ with the help of a local artist and blacksmith – it’s a beautiful iron butterfly, and every child in year 5 at the time designed and made one of the coils of its wings.

But the abolition of the trade in 1807 didn’t mean the end of British slavery. It took another 26 years for the institution itself to be abolished in the British Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape. Why so long? Partly because so many individuals in both houses of Parliament had vested interests in the continuation of slavery.

And true abolition didn’t exactly bring freedom. Due to pressure from the powerful West India lobby, slavery was actually replaced by another kind of unfree labour: former slaves were tied into a fixed term of apprenticeship instead. Meanwhile, although the slaves received nothing, their owners were able to claim compensation for their loss of ‘property’ on a huge scale – over £20 million, paid by British taxpayers, half of which was awarded to ‘absentee’ owners living in Britain. It was an enormous amount of money: the equivalent of 40% of government revenue for a single year in the 1830s. Over the course of five years, over 40,000 different claims were successfully made.

And true abolition didn’t exactly bring freedom. Due to pressure from the powerful West India lobby, slavery was actually replaced by another kind of unfree labour: former slaves were tied into a fixed term of apprenticeship instead. Meanwhile, although the slaves received nothing, their owners were able to claim compensation for their loss of ‘property’ on a huge scale – over £20 million, paid by British taxpayers, half of which was awarded to ‘absentee’ owners living in Britain. It was an enormous amount of money: the equivalent of 40% of government revenue for a single year in the 1830s. Over the course of five years, over 40,000 different claims were successfully made.

Thanks to a new web Encyclopaedia, launched today, you can now find out exactly who these claimants were.  Legacies of British Slave-ownership gives a fascinating picture of the pattern of slave-ownership in the nineteenth-century by making accessible the records of the Slave Compensation Commission. Owners included clergymen and widows as well as bankers and financiers, and they lived in every part of the British Isles.

Legacies of British Slave-ownership gives a fascinating picture of the pattern of slave-ownership in the nineteenth-century by making accessible the records of the Slave Compensation Commission. Owners included clergymen and widows as well as bankers and financiers, and they lived in every part of the British Isles.

As well as a searchable database, the new website gives a real sense of the impact of this compensation scheme on life in Britain. Until relatively recently, this has been a hidden history. The role of slavery on the development of Britain as a modern, industrialist society is clearly both more far-reaching and more complex than has previously been revealed. Here Catherine Hall, a member of the team of academics based at University College London working on this project, convincingly explains the history and legacy of this – politically, economically and culturally – and discusses the difficulties individuals have long had in coming to terms with this aspect of British history. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning makes a particularly interesting case-study.

society is clearly both more far-reaching and more complex than has previously been revealed. Here Catherine Hall, a member of the team of academics based at University College London working on this project, convincingly explains the history and legacy of this – politically, economically and culturally – and discusses the difficulties individuals have long had in coming to terms with this aspect of British history. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning makes a particularly interesting case-study.

Find out more about the two projects – the completion of the encyclopeadia and the new project to analyse the significance of its contents – on the UCL website, where you’ll also discover useful links to projects giving information about the slaves themselves.

This morning I couldn’t resist exploring the new database. The only nineteenth-century English ancestors that I know of in my family were Nottingham stocking-makers, so I wasn’t surprised when the name Syson didn’t appear. I thought I’d better check Dryhurst – it would have been rather a shock to find that my Irish Anarchist great-great grandmother had married into a family who’d made money from slavery.

This morning I couldn’t resist exploring the new database. The only nineteenth-century English ancestors that I know of in my family were Nottingham stocking-makers, so I wasn’t surprised when the name Syson didn’t appear. I thought I’d better check Dryhurst – it would have been rather a shock to find that my Irish Anarchist great-great grandmother had married into a family who’d made money from slavery.

‘Sorry, your search returned no results.’ Phew. That’s the instinctive response. Of course the point of the exercise is to increase understanding rather than induce individual guilt. Should it be another story when it comes to corporate guilt? Here’s a report on the reaction of Rothschilds and Freshfields to the discovery of the firms’ profits from slavery.

And then I wondered about the Lettsom family. Dr John Coakley Lettsom died in 1815, between the abolition of the slave-trade and the act of 1833 which abolished slave ownership in British territories. But it seems that just before he died, he inadvertently inherited about 1,000 more slaves – his son had recently returned to the West Indies and married a wealthy widow there, both of whom soon died. I don’t know what happened to all of these slaves, but Dr Lettsom’s grandchildren certainly seem to have hung onto some of them. There it is in the records: claims for a total of 49 slaves belonging to various members of the Lettsoms of the Virgin Islands, netting John, William and Catherine the tidy sum of 688 pounds 3 shillings and 9 pence. I suspect Dr Lettsom would have been horrified.

between the abolition of the slave-trade and the act of 1833 which abolished slave ownership in British territories. But it seems that just before he died, he inadvertently inherited about 1,000 more slaves – his son had recently returned to the West Indies and married a wealthy widow there, both of whom soon died. I don’t know what happened to all of these slaves, but Dr Lettsom’s grandchildren certainly seem to have hung onto some of them. There it is in the records: claims for a total of 49 slaves belonging to various members of the Lettsoms of the Virgin Islands, netting John, William and Catherine the tidy sum of 688 pounds 3 shillings and 9 pence. I suspect Dr Lettsom would have been horrified.

Category News | Tags: abolition, Catherine Hall, Dog Kennel Hill, Freedom Sculpture, Lettsom, Slavery, UCL

So fascinating! I too got the sigh of relief that my maiden name doesn’t appear, but then actually the guilt that I don’t know much at all about my family history. My mother in law is painstakingly charting her family history back hundreds of years, and I can go back, perhaps, 100. I wish I knew more about who I came from – but then, I do believe, the only thing that really matters is what I’m deciding to do with my time, now.