Darkling I listen

1July 3, 2014 by Lydia Syson

I’ve only heard a nightingale sing once, in a wood near Bristol, when I was in my early twenties. Last Sunday I stood in the dark and listened to a recording made in 1942, in Surrey. This nightingale was ‘pouring forth its soul abroad’ – rather more widely even than Keats’ bird, since it was being broadcast live by the BBC – in a short-lived annual tradition that was about to end. It was broken that night because the engineer realised that his new high-fidelity microphone was also picking up the growing hum of a flight of bombers. Nearly two hundred aircraft were heading for Germany, and he did not want to warn the enemy of the impending raid. Fortunately he continued to record, if not to broadcast, and the result is now part of The Wind Tunnel Project.

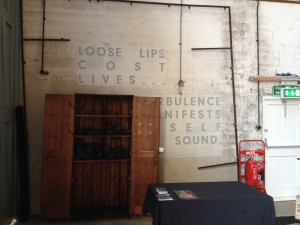

Here in Q121 at Farnborough, rather than Hampstead  or Foyle Riding, my ‘enbalmed darkness’ was not heavy with the scent of hawthorne and eglantine but dank concrete. I pushed my way through immense cold curving fins, a harsher forest than fruit trees. Offered arrowed invitations to ‘explore the light, explore the dark’, I had chosen the dark. The effect was something like walking into a James Turrell installation. It was hard to trust your senses, and took a little courage to step away from the soft shuffle of slippered feet and into unknowable blackness, towards this strange music.

or Foyle Riding, my ‘enbalmed darkness’ was not heavy with the scent of hawthorne and eglantine but dank concrete. I pushed my way through immense cold curving fins, a harsher forest than fruit trees. Offered arrowed invitations to ‘explore the light, explore the dark’, I had chosen the dark. The effect was something like walking into a James Turrell installation. It was hard to trust your senses, and took a little courage to step away from the soft shuffle of slippered feet and into unknowable blackness, towards this strange music.

I was inside the belly of one of the earliest aerodynamic testing facilities in the world. Hawker Hurricanes, like the one that disappears into Romney Marsh in That Burning Summer, were among many well-known aircraft tested here. Thanks to Artliner, the listed buildings are open to the public for just six weeks this summer (closing on 20th July). I was determined to go the moment I read about it.

I was inside the belly of one of the earliest aerodynamic testing facilities in the world. Hawker Hurricanes, like the one that disappears into Romney Marsh in That Burning Summer, were among many well-known aircraft tested here. Thanks to Artliner, the listed buildings are open to the public for just six weeks this summer (closing on 20th July). I was determined to go the moment I read about it.

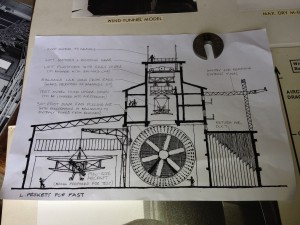

The aeroplanes which once hung in the tunnel, buffeted by a carefully controlled artificial gale, are ghosted in reverse by speakers in the shape of a polished wood gramophone horn, flanked by shapes suggestive of a twin-prop. They face a gigantic mahogany propellor, now still, majestic with the kind of beauty that comes with that perfect union of form and function. As the sound of the bombers intensifies, their high roar is imperceptibly transformed into a chorus of human voices, drowning out the birdsong.

I loved The Wind Tunnel Project for lots of reasons. War has left many architectural markers on this country, constructions that often seem both to scar and enhance the landscape (as Corinna Dean’s new book Slacklands elegantly makes evident). These strange, semi-abandoned cathedrals to flight, now in the middle of a smart business park, were among the most evocative places I’ve been. They will of course affect every visitor differently of course. You might be drawn to an empty control room. An anticlastic curve. A sense of the presence of absence, which even worshippers in the form of extremely talkative technical experts could not dispel when we were there. (They blithely ignored the signs requesting silence.)

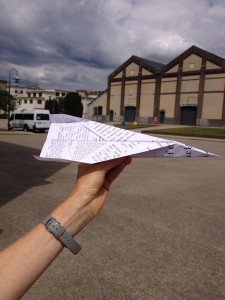

I have a cousin whose father was a test pilot during the war, and was killed in the process. His daughter had hoped to locate the wartime correspondence between him and his brother, Peter Wheeler, my great-uncle, who was an RAF fighter pilot, and survived. This was while I was writing That Burning Summer. I’m still hoping that bundle of letters, which she remembers as tied with a red ribbon, will turn up. It seems, for the time being, to have slipped between cracks in the family, as old letters often do. At The Wind Tunnel Project, I thought of the letters and their authors, just as I thought of Henryk and his paper planes (‘High ceiling, wooden floor, littered with paper.’ TBS p.144) and remembered the days when our own house was filled with drifting origami aircraft, the product of an eight year old’s obsessive experimentation.

A postgraduate student in Information Experience Design at the Royal College of Art, Xinglin Sun, had the idea to give out instruction sheets in this form, which could be released in the smaller wind tunnel in building R52.

When I learned that the first Surrey nightingale was the first BBC ‘Outside Broadcast’ I was also reminded of my own first ‘OB’, a World Service programme which went out live from another cathedral-like structure: the Palm House at Kew Gardens. It included the artist Helen Chadwick, who died a few years later, after contracting a virus during her work on foetal waste. You won’t be surprised to learn that the skeleton of the 1912 airship shed instantly brought Vango, and Hugh Eckener‘s monumental Zeppelins to mind.

Last weekend The Wind Tunnel Project also hosted an exhibition of military art from a number of sources: a contemporary war artist‘s interpretation of Afghanistan, some incredibly impressive ‘A’ level work using bottle tops, safety pins, moss and a flowers to create military jackets that turn into tombs, and material produced in the course of art therapy by soldiers suffering from Combat Stress. LMF – Lack of Moral Fibre – has theoretically been confined to history, although Elizabeth Wein told me earlier this year that an instructor once accused her of it when she was learning to fly and wasn’t keen to take off in bad weather. The Armed Forces take a very approach to such issues now. I thought of Henryk’s lucky Polish stone and Nat’s reflections on fortune at the Ebro when confronted with a sculpture about contemporary soldiers’ superstitions by Polly Hughes called 20% LUCK (2011). Some aspects of going into battle never change. When children ask me, as they often do, why I like writing about war, this is one answer.

Read the full story of the nightingale recordings and their interruption at Public Address, in a brilliant account of archive browsing and ‘convolutes’. Find out more about the wind tunnels and their history at FAST – the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust. If you’d like to encourage the BBC to revive the traditional of annual May broadcasts of cello-accompanied nightingale song, although it’s too late for this year, you might as well sign this petition. You never know, and you’ll find out more about nightingales on the campaign website. The RSPB also offers advice about where to hear nightingales in Britain these days.

IMPORTANT – if you drive to The Wind Tunnel Project on a weekend, you may be misled by the AA signs, so make sure you are definitely going to the postcode on your ticket. And although it’s not very clear from the Eventbrite booking page, children under 12 are free and students/12-18 year olds half price.

Thanks to my brother Luke for contributing some of the photographs!

Category News | Tags: Artliner, Combat Stress, Corinna Dean, Farnborough, FAST, Keats, Nightingale, Outside Broadcast, Slacklands, Spitfire, test pilot, The Wind Tunnel Project

Awesome post.