Citoyennes: women of the Paris Commune

0May 5, 2015 by Lydia Syson

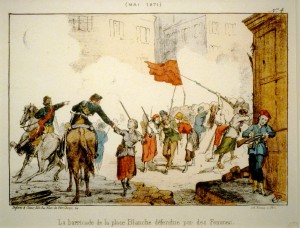

The mythical figure of the pétroleuse, hideous or heroic depending on your point of view, has now almost been forgotten. For decades it was the most abiding image of the 1871 Paris Commune, and undoubtedly helped to hide the true history of real women’s involvement in France’s last nineteenth-century revolution. Edith Thomas broke new ground in uncovering this history with Les Petroleuses (1963), angry yet almost apologetic about the need for a corrective to misogynistic accounts of events coming from both sides of the political divide. I’ve written about the ‘women incendiaries’ for The History Girls this month, and you can find out more about the origins of this myth and see a selection of photographs of suspects taken by Eugene Appert at the website of the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

But who were the real citoyennes of Paris,  and why were so many so loyal in their support of the Commune that they were prepared to risk everything for the cause, even to the bitter end? Inevitably, we’ll never know the names of thousands of the women slaughtered during Bloody Week, nor precisely why or how or where they died or were buried. It’s less difficult to see why they became involved. They had ‘nothing to lose and everything to gain’, as Claudine Rey (president of the Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris 1871) explained in a lecture I attended in Paris in March last year. Working-class Parisiennes lived in truly terrible conditions: a ‘hell of poverty and alcoholism’, in which they faced exploitation of every kind, rising unemployment, derisory and unequal pay, and almost ‘obligatory’ prostitution. Even before the Commune was declared in March 1871, these issues were debated in the political clubs that sprang up as soon as the Second Empire relaxed previously harsh legislation on ‘association’. A new word had to be coined for the women who took to the podium (often a pulpit) to speak: oratrices.

and why were so many so loyal in their support of the Commune that they were prepared to risk everything for the cause, even to the bitter end? Inevitably, we’ll never know the names of thousands of the women slaughtered during Bloody Week, nor precisely why or how or where they died or were buried. It’s less difficult to see why they became involved. They had ‘nothing to lose and everything to gain’, as Claudine Rey (president of the Association des Amies et Amis de la Commune de Paris 1871) explained in a lecture I attended in Paris in March last year. Working-class Parisiennes lived in truly terrible conditions: a ‘hell of poverty and alcoholism’, in which they faced exploitation of every kind, rising unemployment, derisory and unequal pay, and almost ‘obligatory’ prostitution. Even before the Commune was declared in March 1871, these issues were debated in the political clubs that sprang up as soon as the Second Empire relaxed previously harsh legislation on ‘association’. A new word had to be coined for the women who took to the podium (often a pulpit) to speak: oratrices.

Liberty’s Fire was largely inspired by a legend among Communardes, Louise Michel, and the startling discovery that my anarchist great-great-grandmother, Nannie Dryhurst, had worked with her when she lived in London in the 1890s. A truly extraordinary and charismatic revolutionary (shown left and at the top of the page in her National Guard uniform) the so-called ‘Red Virgin of Montmartre’ relished the opportunities offered by the Commune, and threw herself body and soul into its battles. At her trial, she demanded execution: “Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance.” (Edith Thomas)

Liberty’s Fire was largely inspired by a legend among Communardes, Louise Michel, and the startling discovery that my anarchist great-great-grandmother, Nannie Dryhurst, had worked with her when she lived in London in the 1890s. A truly extraordinary and charismatic revolutionary (shown left and at the top of the page in her National Guard uniform) the so-called ‘Red Virgin of Montmartre’ relished the opportunities offered by the Commune, and threw herself body and soul into its battles. At her trial, she demanded execution: “Since it seems that every heart that beats for freedom has no right to anything but a little slug of lead, I demand my share. If you let me live, I shall never cease to cry for vengeance.” (Edith Thomas)

Nor did she. Michel was transported to New Caledonia, returning to Europe after the amnesty of 1880. Rather surprisingly, towards the end of her days she lived in East Dulwich, not far from where I now live, and loved animals as passionately as she did the human race. She had a tendency to romanticise her own life, which has been echoed in representations of her ever since. I can’t pretend Liberty’s Fire is any exception! Michel is the only real citoyenne who appears, in fictionalised form, in my novel, and though it was tempting to include many more, the narrative was complicated enough already, and I had to content myself with fleeting references.

Most of the other leading female figures in the Commune are far less well known. None of these very brief summaries of their lives can remotely do justice to these remarkable women, but I hope you’ll be encouraged to find out more about them.

Russian-born Elizabeth Dmitrieff was only twenty  when Marx asked her to go to Paris to report on the Commune for the International Workingmen’s Association. On excellent terms with both Marx and his daughters, she had arrived in London as delegate of a group of Russian revolutionaries she’d met in Geneva. In Paris she helped set up and led the Union des Femmes, energetically recruiting women ‘new to militancy, and who came from a distinctly proletarian background’ (as Thomas put it). They volunteered as nurses and canteen workers, built barricades and fought for equal rights and wages in the workplace, not least for women engaged in making National Guard uniforms, one of the few forms of employment flourishing. Dmitrieff could hardly have been more glamorous, always wearing an elegant black riding habit with a gold-fringed red silk scarf across her chest and a felt hat trimmed with red feathers.

when Marx asked her to go to Paris to report on the Commune for the International Workingmen’s Association. On excellent terms with both Marx and his daughters, she had arrived in London as delegate of a group of Russian revolutionaries she’d met in Geneva. In Paris she helped set up and led the Union des Femmes, energetically recruiting women ‘new to militancy, and who came from a distinctly proletarian background’ (as Thomas put it). They volunteered as nurses and canteen workers, built barricades and fought for equal rights and wages in the workplace, not least for women engaged in making National Guard uniforms, one of the few forms of employment flourishing. Dmitrieff could hardly have been more glamorous, always wearing an elegant black riding habit with a gold-fringed red silk scarf across her chest and a felt hat trimmed with red feathers.

André Léo was a prolific journalist and novelist, likened in her day to George Sand, who was vehement in her opposition to Pierre-Joseph ‘property is theft’ Proudhon’s entrenched sexism. Her real name was Léodile Béra but she used the names of her twin sons as her pseudonym. A early feminist and activist, in 1868 she published a deeply radical ‘Manifesto’ demanding rights for women, which was signed by eighteen other women and attacked the inconsistencies of the Napoleonic code: ‘Is a woman an individual? A human being?. . . Why is she obliged to obey laws that she has neither made not consented to? Why is she excluded from the right, recognised by all, of choosing her representatives?. . . the rights of the mother are annihilated by those of her husband. Women’s labour, of equal value, is paid half that of man, and often even this work is denied her.’ (Quoted by Carolyn Eichner in Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune.)

André Léo was a prolific journalist and novelist, likened in her day to George Sand, who was vehement in her opposition to Pierre-Joseph ‘property is theft’ Proudhon’s entrenched sexism. Her real name was Léodile Béra but she used the names of her twin sons as her pseudonym. A early feminist and activist, in 1868 she published a deeply radical ‘Manifesto’ demanding rights for women, which was signed by eighteen other women and attacked the inconsistencies of the Napoleonic code: ‘Is a woman an individual? A human being?. . . Why is she obliged to obey laws that she has neither made not consented to? Why is she excluded from the right, recognised by all, of choosing her representatives?. . . the rights of the mother are annihilated by those of her husband. Women’s labour, of equal value, is paid half that of man, and often even this work is denied her.’ (Quoted by Carolyn Eichner in Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune.)

Nathalie Lemel was a co-founder of the Union des Femmes, and another IWA militant, who – like Dmitrieff – criticised the Commune for its failure to promote female suffrage. She left school at the age of 12 to become a bookbinder, and came to Paris from Brittany in search of work after her husband’s alcoholism had bankrupted their business in Quimper, and became a committed strike leader. With Communard Eugene Varlin, she set up a co-operative canteen called La Marmite and was one of the women defending the barricades of Les Batignolles and Place Pigalle, though at her trial she denied being armed: ‘I was satisfied with passing ammunition to the fighters, and giving first aid to the wounded.’ She tried to kill herself after the defeat of the Commune, but was arrested the next day, and deported to New Caledonia. On the voyage out, she met Louise Michel, whom she introduced to anarchism.

Nathalie Lemel was a co-founder of the Union des Femmes, and another IWA militant, who – like Dmitrieff – criticised the Commune for its failure to promote female suffrage. She left school at the age of 12 to become a bookbinder, and came to Paris from Brittany in search of work after her husband’s alcoholism had bankrupted their business in Quimper, and became a committed strike leader. With Communard Eugene Varlin, she set up a co-operative canteen called La Marmite and was one of the women defending the barricades of Les Batignolles and Place Pigalle, though at her trial she denied being armed: ‘I was satisfied with passing ammunition to the fighters, and giving first aid to the wounded.’ She tried to kill herself after the defeat of the Commune, but was arrested the next day, and deported to New Caledonia. On the voyage out, she met Louise Michel, whom she introduced to anarchism.

Paule Mink (Adèle Paulina Mekarska) was born in Clermont-Ferrand to an aristocratic French mother and a Polish father, a count in exile since the unsuccessful 1830 Polish rising. Unlike Léo and Dmitrieff, her path to socialism and feminism was through grass-roots activism and direct democracy: she became well-known as a revolutionary oratrice in the political clubs of Paris in the late 1860s, vehement in her anti-clericism. Alongside Michel, Mink was a member of the Montmartre Committee of Vigilance during the Siege of Paris, and she opened a free school for girls in Saint-Pierre church. She was on a propaganda tour of the provinces during Bloody Week, and managed to escape to Switzerland, where the French police kept tabs on her throughout her exile – only Michel had a bigger dossier.

Marie Ferré, pictured above standing with Louise Michel (centre) and Paule Mink (right), was the sister of Michel’s great friend, the prominent Communard Théophile Ferré. According to Michel’s memoirs, after the fall of the Commune, the Versailles soldiers pressurised their mother into a hysterical fit during which she inadvertently betrayed the whereabouts of her son by threatening to arrest Marie – then bedridden and feverish – in his place. Théophile was found and executed, and his mother died a few weeks later in a psychiatric hospital.

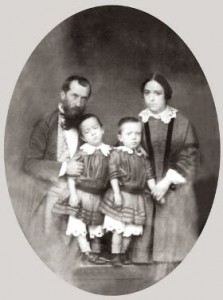

Anna Jaclard – described in 1871 as  a ‘harpy’ and a ‘pétroleuse’ by the secretary of the Russian Embassy in Paris – was born Anna Vassilievna Korvina Krukovskaya. She had a luxurious childhood on her military father’s Russian estate, and both Anna and her mathematician sister Sophie were swept up in the wind of change blowing through educated Russian families in the 1860s. In St Petersburg, Dostoyevsky published her first, pseudonymous work, A Dream, but she turned down his marriage proposal and used a ‘marriage blanc‘ to escape to Geneva, where she fell in love with the French Blanquist Victor Jaclard, befriended Karl Marx and joined the International. They both went to Paris after the fall of Napoleon III in the early stages of the Franco-Prussian war (September 1870), where Anna became active in the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee. Both Anna and Victor Jaclard were captured during Bloody Week, and she was sentenced to hard labour for life in the New Caledonia penal colony to which Lemel and Michel were exiled, while he received a death sentence. But both managed to escape from prison, arriving via Switzerland in London, where Marx gave them shelter.

a ‘harpy’ and a ‘pétroleuse’ by the secretary of the Russian Embassy in Paris – was born Anna Vassilievna Korvina Krukovskaya. She had a luxurious childhood on her military father’s Russian estate, and both Anna and her mathematician sister Sophie were swept up in the wind of change blowing through educated Russian families in the 1860s. In St Petersburg, Dostoyevsky published her first, pseudonymous work, A Dream, but she turned down his marriage proposal and used a ‘marriage blanc‘ to escape to Geneva, where she fell in love with the French Blanquist Victor Jaclard, befriended Karl Marx and joined the International. They both went to Paris after the fall of Napoleon III in the early stages of the Franco-Prussian war (September 1870), where Anna became active in the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee. Both Anna and Victor Jaclard were captured during Bloody Week, and she was sentenced to hard labour for life in the New Caledonia penal colony to which Lemel and Michel were exiled, while he received a death sentence. But both managed to escape from prison, arriving via Switzerland in London, where Marx gave them shelter.

Elisabeth Retiffe, cardboard maker, worked as a cantinière and then an ambulancière or nurse during the Commune and was tried as a pétroleuse in September 1871, alongside Leontine Suétens (a laundress-turned-cantinière who was twice wounded) Joséphine-Marguerite Marchais, Lucie Bocquin (day-labourers) and Eulalie Papavoine (a seamstress who followed her partner’s National Guard battalion as an ambulance nurse everywhere he fought). When asked why she had stayed behind at the Charité Hospital when the battalion fled, Papavoine replied: ‘We had dead and wounded men.’ Despite lack of reliable evidence or witnesses – testimony that identified them as active Communardes related to purely to clothing, pillaging, building of barricades, supplying ammunition, gun-carrying, drinking and providing alcohol to others, but not arson –

Retiffe, Suétens and Marchais were sentenced to death, Papavoine to deportation and Bocquin to ten years solitary confinement. The death sentences were later commuted to deportation with hard labour, possibly thanks to the intervention of Victor Hugo. Retiffe is known to have died in the penal colony of Cayenne. Another woman, Marie Alexandrine Leroy, who was in charge of requisitions during the Commune and looked after the orphans of the National Guard, was condemned simply to deportation to New Caledonia.

The last three photographs, reproduced with the kind permission of the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library, were ‘shot’ while the women were in prison by the Eugene Appert, creator of some of the earliest photomontages. More on Appert and his significance coming soon!

Other Communardes are listed in the preface to Victorine Brocher’s memoir: Maria La Cécilia, Aline Jacquier, Béatrix Excoffon, Blanche Lefèvre, V. Tinayre, Marceline Leloup, Adèle Gauvin, Malvina Poulain, Augustine Chiffon, Deletras, Jarry, JDesfossés, Blin, Poirier, Danguet, Goullé, Smoith, Cailleux, Dupré. These obviously represent just handful of the women involved.

More about Brocher’s book and suggestions for further reading about the women of the Commune can be found here. And here is an article (in French) about Brocher herself (whose husband ended up in Camberwell, where I live, so presumably she did too!).

Join me at the Fitzrovia Festival on June 20th 2015 for a walk around the area and discussion of the activities of a number of other Communards in exile in London, and visit the site of the anarchist international school where my great-great-grandmother taught alongside Louise Michel. Meet at Fitzrovia Neighbourhood Centre, 39 Tottenham Street, Fitzrovia, London W1T 4RX just before 12.

Category News | Tags: André Léo, Anna Jaclard, Citoyennes, Communardes, Elizabeth Dmitrieff, International Workingmen's Association, Liberty's Fire, Louise Michel, Marie Ferré, Montmartre, Nannie Dryhurst, Nathalie Lemel, New Caledonia, Paule Mink, Union des Femme, Vigilance Committee, Women in Paris Commune

Leave a Reply