Len Crome – Autobiographical Notes

0August 2, 2012 by Lydia Syson

Len Crome (1909-2001) was chief of the medical service of the 15th Army Corps of the Republican army during the Spanish Civil War; and a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Army Military Corps during the Second World War, when he was awarded the Military Cross for outstanding bravery. This brief autobiography is published with kind permission of his son, Peter Crome, and offers a fascinating insight into Crome’s life before and after the Spanish Civil War.

I was born on 14th April 1909 in Russia in the town of Dvinsk, later known also as Daugavpils [now in Latvia]. We spoke Russian at home although mother also spoke German and both my parents used Yiddish when they did not want us to know what they were talking about (in vain of course – children understand all languages). Dvinsk was a fortress and garrison town and there was lots of military activity especially after the start of the war. The front was close and I saw the first man killed: a peasant who fell from his cart having been hit by shrapnel from a German bomb.

One day the Tsar visited the front and passed our school. All parents were told to order new uniforms for the pupils. We were lined up in front of the school. Being small and placed in one of the back rows I glimpsed only the tops of the lances of the mounted escort. Then came the revolutions. Life became more exciting. Frequent demonstrations, the double-headed eagle wrenched off the front of school, red banners everywhere that bleached to dirty grey during the summer. I was constantly asked by the grown ups jokingly whether I was a menshevik or a bolshevik. I shared a room with one of my uncles who was only five years older and went to the same school. He played the second clarinet in the school orchestra and would practice ceaselessly the Marseilliase, and later, after October, the Internationale. Soldiers billeted in our house gave me their mounts to ride. The Germans captured the town and the German soldiers gave me their rifles to play with. They also treated me with “esrsatz” honey and jam.

In 1918 the family moved to Libava, later named Liepaja. There I went to the only Russian school in the town from which I graduated in 1926. I was a poor scholar, badly behaved, but was given high marks for Russian and Biology.

My father had business connections in Scotland and I had a friend studying there. I therefore went to study in Edinburgh and qualified as a doctor in 1932. Whilst doing the customary junior jobs war broke out in Spain. I was not a member of any party but read and was influenced by books of the Left Book Club. The events in Germany affected me greatly on account of the anti-Semitism of which I had many previous experiences. I knew that many antifascists went to Spain to help in the struggle against Franco and decided to do the same. Not knowing how to proceed I wrote to Pollitt who advised me to join the Scottish Ambulance Unit. I joined the unit and went with it in the Autumn of 1936. I and three other members of the Unit soon discovered that the aims of our leadership were also to help the fascists who were hiding and we decided to join the International Brigades which were just being formed. We did so with the help of Norman Bethune who took us to one of the IB hospitals. I was soon in the field working as assistant to the Chief Medical Officer of the 35th Division – Domanski-Dubois. He was wounded during the battle of Brunete and I was told to take his place by the General commanding the division, Walter. Dubois was killed later at the battle of Quinto and I became permanent chief of the Division Medical Services. Some of my impressions of this period I published in History Workshop (1980, 9, p116). After General Walter was recalled to the USSR I was made Chief Medical Officer of the 15th Army Corps. All IBers were repatriated in the autumn of 1938.

I was soon working as a GP in Camberwell. At the same time I helped to train first-aid ARP workers in Islington. Another job was to look after medically refugees from Czechoslovakia, with one of them, Helen I fell in love and soon married.

As mentioned I was not a member of any political party in Spain but soon realised the leading part in the fight against fascism was played by communists such as La Pasionaria and Communist officers such as Lister and Modesto. It appeared obvious to me that no successful struggle against fascism and social injustice was possible without resolute and disciplined guidance provided by the communist party and joined it. My first branch was of doctors somewhere in Belsize Park, a few of whom became our lifelong friends. We discussed mainly reform of the medical services and all were at the same time members of the Socialist Medical Association where we took part in similar discussions. Many of the conclusions we and others came to were later incorporated in the NHS.

The start of the German war against the USSR in June 1941 changed everything. I was asked by Madame Maisky, the wife of the Soviet Ambassador, to help in choosing medical equipment for troops in the field and did so. Madame Maisky began visiting factories where the equipment was being manufactured. However now that the political situation changed I was soon called up in the RAMC. After brief training and service as MO [Medical Officer] in Norfolk I was sent in convoy to North Africa.

The military operations in the Mahgreb did not last long. The Germans and the Italians were defeated and we began to prepare for the landing in Italy. I had two special tasks in Algiers. One was to prepare a report for the Army on the state of health of the Algerian labourers who were supplied to our army by the French authorities or more accurately by the French colonial gendarmerie. The state of labourers was lamentable. Underfed, treated barbarously in the camps, suffering from wasting diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria they were glaring evidence of colonial brutality. I prepared an appropriate report. Whether any attention followed is doubtful. My second task was to see whether any help could be arranged for former IBers who managed to escape from France and were now stuck in Algeria. I discovered that this matter was already being dealt with by a mission consisting of Eugene Szyr, who was a representative of the Polish government in the USSR and a man who called himself by the very Polish name of Mickevic but was really a Russian GPU Officer [ie Soviet secret police – the GPU, Gosudarstvennoye Politicheskoye Upravlenie, (State Political Directorate) originally the Cheka, later the OGUP and then GUGB] They were interested in stranded Soviet prisoners of war and Polish International Brigaders. They manifestly distrusted me, a British officer, and I could nothing to change their attitude. Years later I learned from two of those repatriated by them that on landing on Soviet soil all were rounded up by the GPU, taken to prisons and gulag camps, and hardly anyone survived. One of the survivors is my friend Dr Ersler who spent 11 years as a prisoner in Soviet jails.

After landing in Sicily, the first large city captured on the main land was Naples. Thereafter began a slow northward advance blocked for a while by almost every river and ravine. The main obstacle on the way to Rome proved to be Monte Cassino, a hill with a large Benedictine monastery at the top. It was heavily manned and fortified by the Germans and held us up for a long time. The final assault was by us and the Polish forces on the right. Our starting line was a rather broken up lane encircling the fold of the hill. I established our field ambulance post on the side of the lane along which we could send the casualties after first aid back to the field hospital. Across the lane was another field ambulance post but their medical officer was soon killed by a mortar bomb so that it was up to us to clear all casualties. The lane was rather heavily under fire but we were lucky: only one member of our team suffered shell shock and had to be evacuated. For this action and to my great surprise I was awarded an “immediate” Military Cross and was a few weeks later presented to the King.

After crossing the River Po on 5th May 1945 I found myself acting as supervisor-commander of a very large German military hospital for their Russian soldiers. This job only lasted a week or so, then I was sent across the Alps to supervise the medical state of the Cossack army that fought for the Germans. Since they now lived in the open, often with their families and children, we feared that epidemics might occur. We need not have worried; they were past masters of living on the land (and off the land). In this role I had also the task when the time came to ensure medical cover for them when they were handed over to the Soviet Army. My experiences of this period I described briefly in the weekly News and Views. After that I was ordered to supervise the military arrangements of German military hospitals in our zone in Austria with some 30,000 patients in them. At this time I was allowed to have my wife and family with me and we established ourselves in Villach. In 1946 I was posted to Italy, at first as Chief Medical Officer in the District of Riccione near Rimini, and later as commandant of our military hospitals in Naples. The hospital was later transferred to Caserta. Our younger son Peter was born in our hospital in the town. In the autumn of 1947 I was demobilised and we returned to London.

Already, whilst in the army, I learned that our family remaining in Liepaja were killed by the Germans. Father had earlier been deported by the GPU to one of the northern labour camps. Being over 70 he was unable to fell the necessary quota of timber and was not able to qualify for the proper ration of bread. He died in the camp probably as the result of starvation. Fortunately my brother and one of my sisters were in London alive and well.

I should have mentioned earlier that while in Riccione I was also concerned with the medical supervision of the Ukrainian prisoner of war camp. The Western Uniate Ukrainians embraced enthusiastically the Nazi ideology during the occupation, gladly participating in the pogroms of Jews and even formed voluntarily their own SS division – the SS Galizien. That division was destroyed in battle by the Soviet army but another one – the 4th Ukrainian division – was formed in its place. They fought against us in Italy and eventually surrendered at the end of the war and were kept by us in a camp in Riccione. They were not handed over to the Soviet army but were sent over to the UK were they worked at first on the land and were later freed. Many married English girls and their children formed Ukrainian nationalist societies.

I had long wanted to become a pathologist and after return to London obtained a trainee post at St. Mary’s Hospital, where I worked in the pathology department headed by Professor Newcomb and in the bacteriology department headed by Professor Alexander Fleming. Later I trained in neuropathology at the Maudsley hospital headed by Professor Meyer. Becoming a pathologist meant also taking higher examinations that I passed later in Edinburgh.

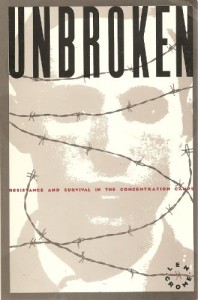

Most of my social activities were with the SCR [Society for Cultural Relations between the Peoples of the British Commonwealth and the USSR, founded in 1923] where I was for some years Secretary of the medical section and subsequently Chairman of the Society. In that role I visited on several occasions the USSR. My most lasting memory of those visits was a trip to Tolstoy’s estate of Yasnaya Pollana and seeing the simple grave of the writer, the sight of which will always remain with me. As well as many papers and a few books on pathological subjects I wrote a book on resistance in German concentration camps, Unbroken, the chief protagonist being my brother-in-law – Jonny Huttner – who was a prisoner in three of the camps for 9 years. On reaching the age of 65 I retired from the NHS and worked as locum pathologist in many hospitals including three years at the University of Amsterdam. For the last 5 years I have been Chairman of the IBA [International Brigade Association, which became the International Brigade Memorial Trust]

Most of my social activities were with the SCR [Society for Cultural Relations between the Peoples of the British Commonwealth and the USSR, founded in 1923] where I was for some years Secretary of the medical section and subsequently Chairman of the Society. In that role I visited on several occasions the USSR. My most lasting memory of those visits was a trip to Tolstoy’s estate of Yasnaya Pollana and seeing the simple grave of the writer, the sight of which will always remain with me. As well as many papers and a few books on pathological subjects I wrote a book on resistance in German concentration camps, Unbroken, the chief protagonist being my brother-in-law – Jonny Huttner – who was a prisoner in three of the camps for 9 years. On reaching the age of 65 I retired from the NHS and worked as locum pathologist in many hospitals including three years at the University of Amsterdam. For the last 5 years I have been Chairman of the IBA [International Brigade Association, which became the International Brigade Memorial Trust]

Listen to Len Crome talking about his work in Spain at the Imperial War Museum, London. (NB. Search under Leonard Crome.) The Len Crome Memorial Lecture is held by the IBMT each March, usually in London or Manchester.

Category Reviews & more | Tags: Autobiography, Chief Medical Officer, IBMT, International Brigades, Len Crome, Leonard Crome, Memorial Lecture

Leave a Reply