‘Resist the attempt to construct an argument’

2October 19, 2015 by Lydia Syson

This slogan flashed by while I sat enthralled by William Kentridge’s video installation Notes Towards a Model Opera at the Marian Goodman Gallery in Soho, London. It made me smile because I now spend two days a week as a Royal Literary Fund Writing Fellow at the Courtauld Institute for the History of Art encouraging students to construct an argument. Yet when I’m writing fiction, arguments are something I know I have to resist, despite my political themes.

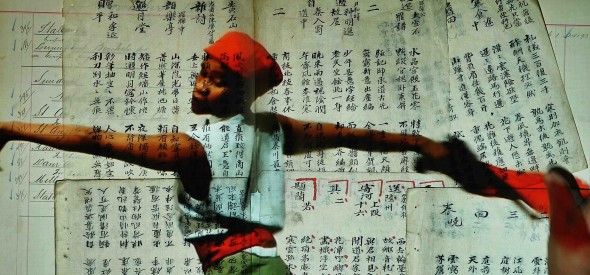

Notes Towards a Model Opera forms part of a mesmerisingly immersive show which spoke uncannily to many of my current and long-term obsessions, articulating but not arguing its ideas with profundity and panache. Words and images, repeatedly and rapidly overlaid, appeared and vanished with strobe-like intensity. I recognised photographs of Communards in open coffins, pages from the Commune’s official newspaper, ink-wash Manet-esque flowers flying away on scattering printed pages, calligraphy transformed itself into doves in flight. I may have seen the scribbled words of Marx – a reference to Parisians ‘storming heaven’. I’m sure I saw maps of China, of Africa in Russian, of the Paris suburbs. A megaphone reminded me of the conical hats of the Spanish Inquisition or the Klu Klux Klan. Meanwhile two dancers performed balletic propaganda to a soundtrack constructed of different versions of the Internationale – a jaunty ‘period’ brassband, a lone Chinese voice, a South African protest song.

I’ve written elsewhere about the emotional significance in my writing of the Internationale, the socialist anthem we sang at both my grandparents’ funerals, and which I now sing each year if I possibly can at the annual commemoration of the International Brigades on London’s South Bank: it was the song that united anti-fascist volunteers from just about every corner of the world during the Spanish Civil War. The lyrics were written just after the fall of the Paris Commune. This discovery set me off a few years ago on the trajectory that led from A World Between Us to Liberty’s Fire, from 1936 to 1871.

Opera became a driving force of the plot of Liberty’s Fire for all sorts of reasons. My earliest impressions of nineteenth-century Paris were layered from from performances I’d seen of La Traviata, La Bohème, Manon Lescaut. Participants in the Commune on both sides of the political divide frequently perceived the events in which they were caught up as ‘operatic’ in nature, and many Communards played up to this, performing their political duties in elaborate costume, relishing the drama involved. Making reference to Madame Mao, and also China’s current impact on Africa, Kentridge evokes the sense of revolution as musical spectacle – and vice versa – quite brilliantly. The Commune used opera as a tool of revolution, embracing ‘high’ as well as ‘low’ musical art forms to raise funds, maintain morale, and open up all of Paris to its whole population, rich and poor. Delphine Mordey, whose work introduced me to these ideas, (details here) argues that in staging (or attempting to stage) musical events at the Tuileries and the Opéra, the workers’ government ‘frequently described. . .as barbaric and primitive, sought legitimation through the appropriation of the space and culture of the ousted ruling classes. Ultimately this plan would backfire: far from being taken seriously, the Communards would be described by their critics as little more than characters in their own operatic drama.’

‘Attempting to stage’ is significant, as Kentridge is undoubtedly aware. Extracts from the Commune newspaper, the Journal Officiel, printed in this show on the torn-out-and-glued together pages of an encyclopedia, include a notice addressed to ‘artistes musiciens’. It invited the orchestral musicians of Paris’ musical theatres to an important meeting at the Opéra at 2 pm on Monday 8th May. I suspect this was the meeting to plan the performance to be staged there on May 21th, which included the last act of Il Trovatore. I took the liberty in Liberty’s Fire of giving the part of Leonora in to my character Marie. I don’t want to spoil anyone’s enjoyment of the book by saying here what actually happened.

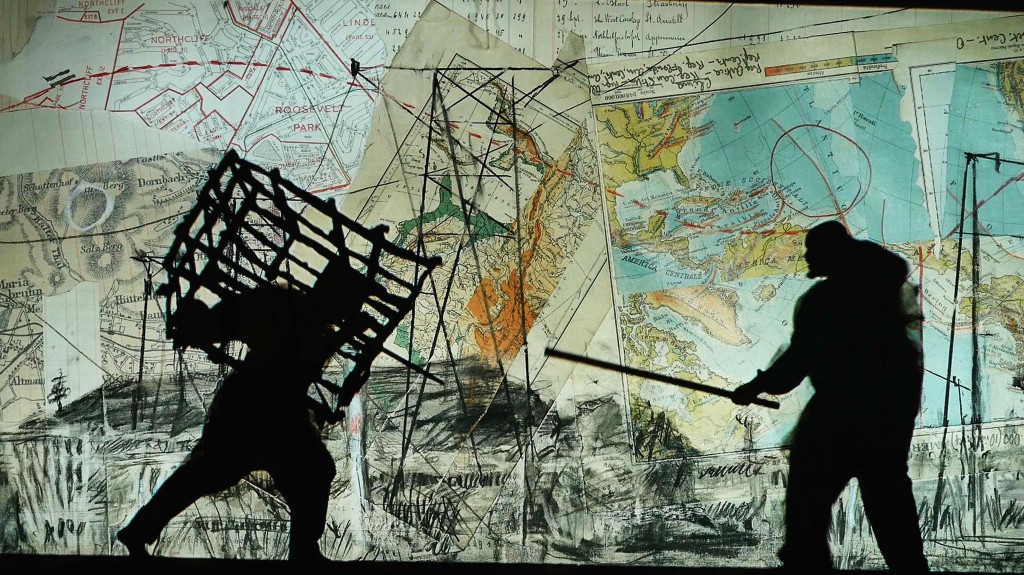

Print, palimpsest, occupation. One thing leads to another. One revolution is overlaid by the next. Here and even more so in the the upper gallery, which is dedicated to a second installation, More Sweetly Play the Dance, still more monumental and ambiguous, the abiding impression is one of progression without progress, though not devoid of hope.

A procession of figures appears, many carrying images we have already seen downstairs. A brass band, a trio of skeletons, orators, stenographers at work, patients dragging their drips…all dance off into the unknown in a style that is stately and medieval-macabre, and I can’t take my eyes of Dada Masilo, the lone uniformed dancer who brings up the rear, duetting with her weaponry as she also does in Notes towards a Model Opera. With just a few touches of red, More Sweetly Play the Dance unfolds like grisaille in motion across an empty, charcoal-drawn veldt landscape. It’s reminiscent of an early nineteenth-century panorama, an art form historically seen as both deceitful and sublime. It’s impossible not to think of the thousands of refugees making their way, with great dignity, across the world at this moment.

This exhibition runs until 24th October at the Marion Goodman Gallery, 5-8 Lower John Street, London. Here’s an interview with the artist by Emma Crichton-Miller in Apollo magazine. Find out here where you can watch Kentridge’s production of Berg’s Lulu ‘Live from the Met’ on November 21st.

All images:

Copyright: William Kentridge

Courtesy: The artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE

Notes Towards a Model Opera, 2014 -2015 3-channel video installation, sound

HD video 1080p / ratio 16:9

Duration 11 minutes 14 seconds (includes credits)

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE

More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015

8-channel video installation with four megaphones, sound

HD video 1080p / ratio 16:9 duration 15 minutes (includes end credits)

Copyright: William Kentridge

Courtesy: The artist and Marian Goodman Gallery Photo Credit: William Kentridge studio

On another note entirely, I’m delighted to say that the 2016 Carnegie award nomination list was published today, and that Liberty’s Fire is on it. Many thanks to all the brilliant and committed librarians who work so hard to make both the Carnegie and the Kate Greenaway medal the most valued and prestigious of all the children’s book prizes in this country. A great honour.

Category News | Tags: Art, Carnegie, Cultural Revolution, Dada Masilo, Liberty's Fire, librarians, Marian Goodman, More Sweetly Play the Dance, Notes Towards a Model Opera, opera, Paris Commune, Revolution, William Kentridge

Great blog Lydia and also congratulations on the Carnegie Nomination. I’m a great admirer of William Kentridge’s work. Have you seen UBU and the Truth Commission which is on at The Print Room Main Theatre… the Hand-spring Puppet company (of Warhorse fame) and Kentridge’s UBU creation. I’ve booked for next week.

Thank you so much Dianne. I’ve not seen UBU and I don’t think I’m going to be able, but I’ll be really interested to hear what you think of it, and whether you feel the show has stood the test of time. I also love Handspring – enjoyed their Midsummer Night’s Dream a few years ago very much.