Unbelievable?

4June 6, 2013 by Lydia Syson

‘Isn’t that rather implausible?’

I’ll take a bet that if you write vampire novels or fantasy or dystopia for young people, that’s not a question you get asked very often. But credibility is important for all kinds of writing. When it comes to historical fiction, it’s a must.

There’s just one problem. A huge part of the pull of writing about the past is delight in the extraordinary stories you find there. Take the eighteenth-century doctor who designed a live-turtle-dove-topped electrified bed which played music as its occupants made love – Dr James Graham also lectured the cream of London society on ice-cold post-coital bathing of the genitals and indulged in earth-bathing. Or the peasant who was inspired by Robinson Crusoe to cross West Africa and the Sahara in disguise, and became the first European to enter Timbuktu and survive  to tell the tale, only to be caught up in Anglo-French political rivalry and accused of theft and deception. My latest YA novel, out in October, is inspired by the incredible journeys made by airmen in the Polish Air Force to continue the fight ‘for their freedom and ours’, and the fighter planes which plunged 30 feet or more into the ground when they crashed during the Battle of Britain, whose pilots were buried with them.

to tell the tale, only to be caught up in Anglo-French political rivalry and accused of theft and deception. My latest YA novel, out in October, is inspired by the incredible journeys made by airmen in the Polish Air Force to continue the fight ‘for their freedom and ours’, and the fighter planes which plunged 30 feet or more into the ground when they crashed during the Battle of Britain, whose pilots were buried with them.

In the case of A World Between Us, I thought particularly long and hard about Felix’s escape in Paris. The woman who first got me interested in the Spanish Civil War convinced me that it could have happened: the funniest, cleverest and most committed of all the Mitford sisters, Jessica. She’s long been a heroine to me. Months after finishing writing my novel, I couldn’t have been more thrilled to discover that her top Desert Island Disc choice was ‘The Peat Bog Soldiers’, the song Kitty teaches Felix as they travel through Spain.

Jessica Mitford’s story is wonderfully told in her autobiography Hons and Rebels and it’s well known. Barely a week after having met and fallen for her cousin Esmond Romilly (and the Spanish cause too), they ran away to Spain together. She told her parents she was staying with friends in Dieppe. When I first read the book as a teenager, it established a gold standard for romantic elopement for me. Clearly, politics didn’t get more passionate than in the Spanish Civil War.

Jessica Mitford’s story is wonderfully told in her autobiography Hons and Rebels and it’s well known. Barely a week after having met and fallen for her cousin Esmond Romilly (and the Spanish cause too), they ran away to Spain together. She told her parents she was staying with friends in Dieppe. When I first read the book as a teenager, it established a gold standard for romantic elopement for me. Clearly, politics didn’t get more passionate than in the Spanish Civil War.

But plenty of forgotten activists volunteered to fight or nurse for Spain with equal spontaneity. The artist Felicia Browne was on a driving holiday through France and Spain with her friend Edith Bone when the military coup that started the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. By the 3rd August she had joined a militia and was on her way to the front, the only British woman actually to fight in the war, and the first of over 500 British volunteers to die. She was killed within three weeks, apparently shot dead while trying to help an injured Italian comrade during an ambushed attempt to blow up a rebel train.

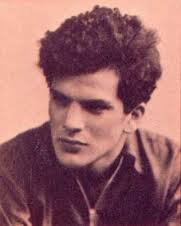

An equally tragic and heroic figure is John Cornford, whose  moving poem ‘Heart of the Heartless World’ is printed in A World Between Us. A committed Cambridge communist, he arrived in Spain on August 8th 1936 as a journalist, but quickly decided that as he didn’t speak a word of Spanish, he’d be rather more valuable fighting than writing news reports.

moving poem ‘Heart of the Heartless World’ is printed in A World Between Us. A committed Cambridge communist, he arrived in Spain on August 8th 1936 as a journalist, but quickly decided that as he didn’t speak a word of Spanish, he’d be rather more valuable fighting than writing news reports.

Felicia Browne had been heading for Barcelona for the alternative People’s Olympiad, planned as an alternative to the ‘Nazi’ Olympics in Berlin, but aborted at the outbreak of war. Two Jewish garment workers from Stepney, Nat Cohen and Sam Masters, were cycling to Barcelona when they heard the news of the uprising, immediately joined the militia, and Nat Cohen became Esmond Romilly’s commander in the Tom Mann Centuria. Another artist, Wogan Phillips, who was  then married to writer Rosamund Lehmann (Invitation to the Waltz, Dusty Answer, The Echoing Grove….), was also on holiday in Spain when war broke out. The Eton-educated son of a wealthy ship-owner, he immediately offered his services to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, bought a van, loaded it with medical supplies, and drove to the Jarama front.

then married to writer Rosamund Lehmann (Invitation to the Waltz, Dusty Answer, The Echoing Grove….), was also on holiday in Spain when war broke out. The Eton-educated son of a wealthy ship-owner, he immediately offered his services to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, bought a van, loaded it with medical supplies, and drove to the Jarama front.

Once the International Brigades had been formed, Paris became their organising centre and the city secretly began to throng with ‘volunteers for liberty’ from all over the world. Scottish volunteer John Lochore was one of many to arrive on a weekend excursion ticket in the winter of 1936:

‘…we duly arrived in the French capital and on leaving the station, by presenting our secret address to the driver, we were whizzed through a maze of streets…I am sure the entire fleet of taxi drivers in Paris knew the address – a fact which was revealed by their casual confidence in conveying us to our “secret destination”.’

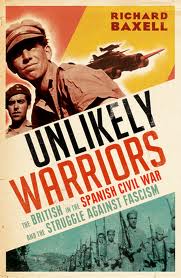

John Sommerfield, a young Communist novelist from Hampstead, was early to sign up at the Place du Combat. Of the many stories grippingly told and quoted by Richard Baxell in his recent book Unlikely Warriors, Sommerfield’s is one of the most amusing:

John Sommerfield, a young Communist novelist from Hampstead, was early to sign up at the Place du Combat. Of the many stories grippingly told and quoted by Richard Baxell in his recent book Unlikely Warriors, Sommerfield’s is one of the most amusing:

‘We advanced to the table, said our piece, were handed forms, and went through complications of translations. What was my job? Author, perhaps? The French word was écrevasse? Something like that. But no, it turned out to be écrivain. Ecrevasse was a lobster. “Sommerfield, the celebrated English revolutionary lobster.” It was a crack to last for weeks.’

Between leaving Glasgow and arriving in Paris. Steve Fullarton aged from eighteen to twenty-one. He was one of the hundreds (former milkmen, maths lecturers, actors, sailors…) who risked arrest and endured a terrifying night climb of the snow-capped Pyrenees in rope-soled sandals, smuggled into Spain because volunteering had become illegal according to the terms of the Non-Intervention Policy.

As Baxell writes, some volunteers came by sea, jumping ship at Republican ports such as Barcelona and Valencia, facing torpedoes from Italian submarines in the Mediterranean. A few travelled in style – Percy Ludwick was recruited in Moscow and flown into Spain, and nurse Patience Darton was also jetted in at speed.

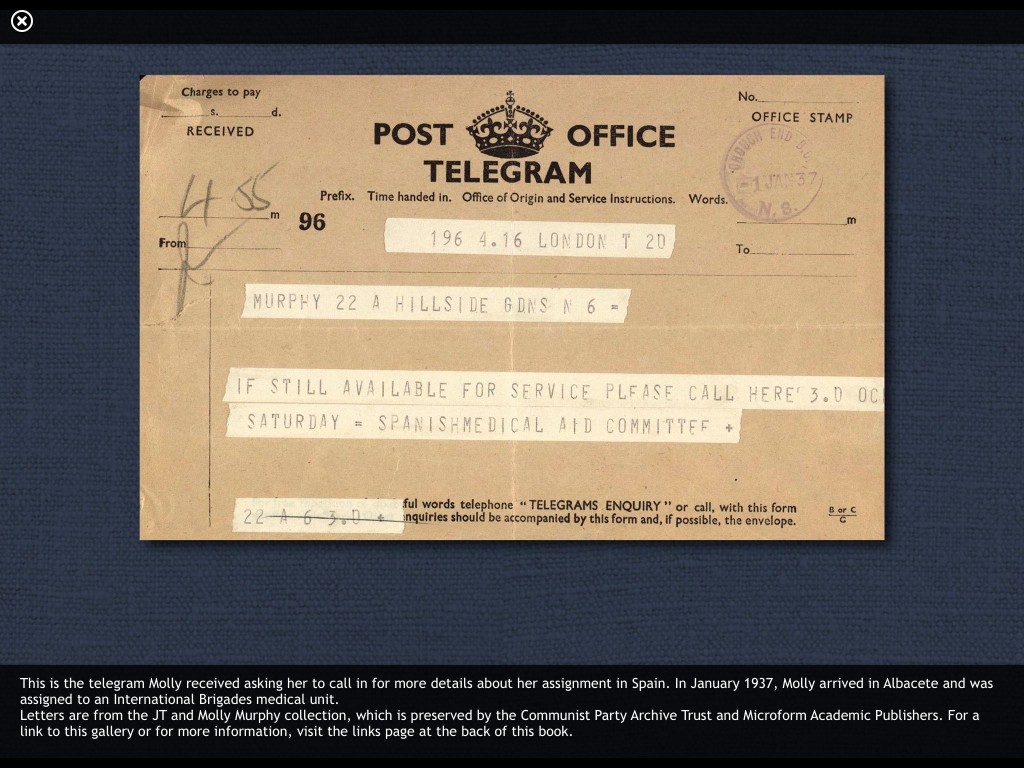

Typically, medical staff had little notice. Molly Murphy, whose letters feature in the multitouch iBook edition of A World Between Us , said the appeal for nurses ‘rang a bell in my heart‘. She felt it would be ‘nauseating’ to continue the private nursing she was doing ‘when splendid young men were dying on the international battlefields of Spain because there were so few nurses and doctors to help keep them alive.’ But soon after being accepted, she was told that no more medical personnel were needed in Spain. Then the telegram arrived:

Juggling the demands of pace, excitement and credibility is quite a challenge when you’re writing for a younger audience. Of course, one of the great advantages of teenage heroes and heroines is that they are at just the age when risk-taking is the norm. Who hasn’t had a good few ‘Did-I-really-do-that?’ moments in their own teenage past? But not many are likely to match the unbelievable spontaneity of so many of the volunteers who rallied to the cause of Spain in the 1930s.

Find out more about the real volunteers who supported the Republican Government in Spain in the 1930s in Richard Baxell’s Unlikely Warriors: The British in the Spanish Civil War and the Struggle Against Fascism, (shortlisted for the Political History Book of the Year, 2013). Angela Jackson’s British Women in the Spanish Civil War was an important source for me while writing A World Between Us. Two more recent publications, Salud! British Volunteers in the Republican Medical Service During the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 by Linda Palfreeman and ‘In Spain with Orwell’: George Orwell and the Independent Labour Party Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War by Christopher Hall, offer new insights on these particular groups of volunteers.

Category News | Tags: credibility, Esmond Romilly, Felicia Browne, International Brigades, Jessica Mitford, John Sommerfield, Molly Murphy, Paris, People's Olympiad, real volunteers, Running away, Steve Fullarton, Wogan Phillips

So many fascinating stories here – and photographs – what a treasure trove – thanks!

Good post. I think you’re absolutely right and I found the description of Felix’s flit from Paris perfectly believable. It was a time when ordinary people performed extraordinary deeds.

A good post but it’s worth noting that volunteers with varying degrees of idealism fought for the other side as well.

There isn’t much information on the internet but Christopher Othen’s book ‘Franco’s International Brigades’ has lots of stuff about them.

Yes, indeed, a fact that younger readers today might find even more unbelievable. Priscilla Scott-Ellis is an interesting case in point. Although her published Diary ‘The Chances of Death’ isn’t that easy to get hold of, Paul Preston includes her as one of four case-studies in ‘Doves of War: Four Women of Spain’.